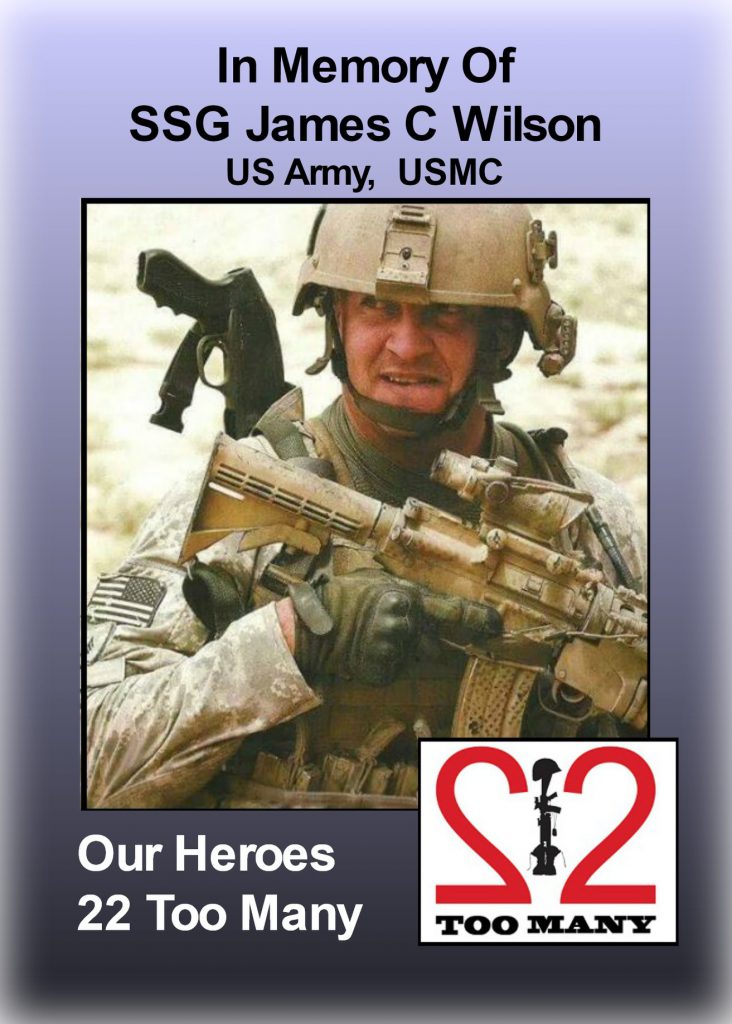

When my unit returned from its Operation Iraqi Freedom mobilization, I had a conversation with my friend, Jimmy. I came home early due to a custodial matter, but we stayed in touch for the duration of the tour. He did well, he really came alive in Baghdad. He wanted me to volunteer and come with him for the Afghanistan mission with another unit from the Pennsylvania Guard. For a variety of family reasons, I could not, but I wish I would have. He was a good friend and a cunning warrior.

Shortly after his return from Afghanistan—we hadn’t reconnected—after wrecking his vehicle, while waiting for responders, Jimmy took his sidearm and took his own life. There’s been a lot of speculation in the decade-plus that’s followed. Many think PTSD.

I’m never sure about that diagnosis. Jimmy was a loud, obnoxious, prior-service Marine with a heart of gold buried deep. I often share the story of what a soft touch he was with the citizens of New Orleans when we helped out in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

I think that in many cases, it’s the return to the mundane that does many soldiers in. The sharp contrast between The Most Important Thing You Will Ever Do In Your Life that comes with wartime service and the rest of your world after. It was something my late, great-uncle, a Marine veteran of Iwo Jima and Guadalcanal, warned me of, the sense that the only noble purpose he would ever have boils down in his own words, “in how many Japs I killed and how many friends I lost until we won.” He found the truth: a life well-lived and enjoyed, being a husband and a father, far surpassed the horrors of war in terms of nobility.

What dignifies and reflects your belief in God? This question posed by my great uncle was expressed somewhat differently, but that’s what I took away from his letters to me when I was in infantry school.

I think Jimmy couldn’t detach his assumed value from being wound up in his martial professions. With the possibility of consequences in the Guard and in his job as a police officer for drunk driving, I don’t think he could see his worth extending beyond the immediate troubles. I wish he could have asked any one of his good friends for help.

And while we honor him, Memorial Day ends up being a paean to the virtues of sacrifice in combat. Jimmy may be mentioned, but there’s always going to be an asterisk. He’s fodder for anti-suicide campaigns, but in that he’s only a pitiable figure, not a resolute combat leader that bravely led successful missions and brought his men home safely.

*

She sobbed in the passenger seat of my car.

I drove her to a town an hour away where she faced a hearing for driving under the influence. We managed to get things transferred to the Lancaster County Veterans Court.

Rabbi Jack Paskoff of Shaarai Shomayim in Lancaster pushed me towards this a few years before, in a role as a “veteran mentor.” He knew I was looking to act on the open wound that was Jimmy’s suicide, and my own struggles with overseas service. A local judge, whose wife was a member of the congregation, was standing up a diversion program specifically for veterans in our county, an opportunity to give them a second chance rather than saddle them with felonies and misdemeanors that would follow them. All a veteran had to do was have an honorable discharge; combat veterans were not the sole recipients of this legal largesse. As a mentor, I was like an AA sponsor, helping them stay on a path of sobriety, helping them with a restorative justice project that was required, and if they had license suspensions or probationary sanctions, helping them deal with those.

I had some qualms about giving people who served in peacetime a chance when there were veterans whose criminality was directly associated with their service, until I met this young woman. As more female and trans veterans came through the program, it became obvious that a court modeled after drug court or a 12-step program was not going to be sufficient for helping those with Military Sexual Trauma. She never deployed, but she suffered greatly at the hands of her fellow Marines. This program was never going to help this young woman so long as it forced her to relive the trauma of her rape, the details of which are only ever her story to tell. And what was done to her cost her so much, including a presence in her children’s’ lives.

That day that she cried in my car, I worried that she’d opt out on living in the same way so many of my friends have. Today, she is doing well. She is health and happy, and it’s not because of anything the system has done for her. It’s her own strength, and reuniting with her community and family.

That time I spent with her was deeply affecting. I decided after that I would strive to make a difference as a non-commissioned officer, especially after I moved from infantry, which was all male at the time, to logistics. I took my final break in service from 2020-2022, during which a former soldier contacted me about her own rape, and the insufficiency of the Maine National Guard’s response was exposed by the Bangor Daily News. When I came back in the service in 2022, I was told during my initial counseling in my unit that some felt “I had betrayed the Guard” in both speaking to the paper and testifying before the state legislature about the culture of misogyny I witnessed. In many ways, I wear that like a badge of honor. Very few male soldiers speak up or spoke up about what they’ve seen or done themselves, or their own status as survivors of sexual assault. It’s something I see improving in terms of training and a “see something, say something” culture in uniform.

During my testimony, I told a highly personal experience of my assault, when during a hazing ritual 30 years ago at the 101st, I was subject to an act of a sexual nature, causing humiliation and bleeding. I hadn’t spoken of that in 25 years. I even became close with my team leader, who did it. It’s a strange, horrible thing, and I am glad our military culture is reshaping itself. We’re trying to drive a stake through the heart of the “good old boy” system, and it’s working.

Nevertheless, I still see the cost to people still harmed by toxic culture every drill weekend. I hear it in the voices of survivors who will never see justice.

I’ve become treasurer of The Sisters in Arms Center, Maine’s only female veteran focused transitional living. We’re working hard to provide a home for female and trans veterans, but we’re also trying all the time to expand our services to survivors of Military Sexual Trauma. Most of my work centers on budgeting and fundraising. The heavy lift is done by our Executive Director, who also is a commissioned member of the Maine Army National Guard. It’s purposeful work, and while I hate that there’s a need for it, it’s not a legislative priority, in spite of the attention on it for over a decade, and funding is in short supply. Outpatient services from the VA are difficult. The reporting system, to my mind, is still broken, especially in the Guard or Reserves.

We held a well-attended viewing of a documentary about Vanessa Guillén at Congregation Beth Israel in Bangor. I invited speakers from the military and agencies. The needle moves slowly. I worry it will be lost when the committed leaders with immediate command of soldiers move on to new roles. It’s an institutional change that has to be embraced in the same way we treat each generation as having left Egypt themselves.

We don’t even mention survivors of MST on Memorial Day. Their service cost them so much, and yet, we’re squeamish about raising the subject.

*

These are among the reasons why I struggle with the ceremonies of Memorial Day. Whether it’s the somber pomp and circumstance of a parade or memorial service, or the festive beginning of summer motif, I feel like there’s so much that was lost to remember.

It’s that the Reservist or Guard member that deployed, fought, and bled in a Baghdad neighborhood and goes back to an unremarkable career as at best box store middle management, drinking himself to death and driving loved ones away.

It’s that a woman who was gang raped and driven from the service by the trauma has to watch people who assault her honored with awards and retirement ceremonies.

You can only hear “freedom isn’t free” by a young essayist so many times before you realize our memorials are as superficial as our concern for an all-volunteer force that is still immersed in a military action that started 23 years ago. People are often surprised to find out soldiers are still deploying to active combat zones on the same Congressional Authorization for Use of Military Force that kicked off our invasion of Iraq.

And it’s that much more acute when it comes on the heels of Yom HaZikaron. Israel puts us to shame with how it memorializes its war dead and the cost to its veterans.

Every year, I find it harder and harder to abide the way we do Memorial Day. So I retreat to the woods, and dwell on it by myself standing atop a mountain or by a wilderness brook.

This year, I’m trying something new. I wrote my thoughts on how Judaism has a salve for moral injury a few years ago, an idea I continue to refine. Now I’m combining it with enrollment at the Pluralistic Rabbinical Seminary in pursuit of smicha.

Years and years ago, I finished daf yomi at Siyum HaShas in 2005. I tried my hand at hadar with Chabad Lubavitch, but the movement wasn’t for me any more than the life of a shaliach, though it took me fifteen years to figure that out. While Leah and I maintain a kosher home and live very Jewishly, inhabiting leadership roles within our community, affixing a label to what kind of Jews we are is less important than producing measurable results in our Jewish community and its intersection with the local non-Jewish world. With the influence and help of two non-Orthodox rabbis I hold in high regard, I was accepted into PRS’ program this year. I want to work on combining the concepts of hitbodedut and the answer Judaism has for trauma in ways that help Jews and non-Jews alike.

We have the tools in our tradition to do this with. Gemilut chassadim, tzedakah, study of Torah, or a combination of these things “avert the decree” during the Days of Awe, but they also carry manifest obligations. We are explicitly told what we must do in the rhetorical question posed by a High Holy Days haftarah, “is this the fast I seek?”

There’s Rambam, too, with his semi-Aristotelian “golden mean.”

Those substantive tools and concepts may help others get through trauma, in no small part because our traditions have been shaped by millennia of hard times. I hope to bring that to bear as part of my capstone project, expanding on Nachman of Breslov’s hitbodedut in a manner tightly wound with our tradition and ritual to help others. There is so much work to do to ply our tradition to sexual assault, which is problematic when it comes to rape—the penalty in Torah is unfathomable today—but October 7th reminds us it is not new to us. How we heal is so important.

*

On the clearest days, with the bluest of skies, and the most aesthetic punctuation of fluffy, white clouds, I stood atop Sunday River Whitecap in Maine and cried.

The wind was blowing strong. I adjusted my hat so it fit snugly against my scalp. From the top of this beautiful peak, I could see the White Mountains in New Hampshire and Maine, the Mahoosuc Range, the valley carved by the Androscoggin River, and the nearby Sunday River ski resort. It was so beautiful.

This year I picked the Grafton Notch Loop for my Memorial Day weekend outing. I invited others, but everyone had other plans or limitations. Ultimately, this was fine. I was grateful for the solitude.

I remembered something from Man is Not Alone by Abraham Joshua Heschel.

We can never sneer at the stars, mock the dawn, or scoff at the totality of being. Sublime grandeur evokes unhesitating, unflinching awe. Away from the immense, cloistered in our own concepts, we may scorn and revile everything. But standing between earth and sky, we are silenced by the sight.

Today I feel residual awe. Today I feel like the world was created for me. And if it was created for me, it was created for Jimmy. It was created for every survivor of MST.

How is there space for self-revulsion and self-hatred when we realize we’re a part of a beautiful Creation?

I know it’s very reductionist to assume that if I could have stood Jimmy on a mountain top on a clear day, that he’d still be with us. Nor could a mossy forest floor undo the damage done by rape.

Finding a Jewish answer to these things is possible. I know time spent outdoors, reconnecting with natural beauty, is a catalyst for finding goodness within ourselves. Perhaps I can come one day soon to Memorial Day and feel like I have a contribution in the face of the things I hate.

Until then, I will honor my friends by saying their names into the wind upon a mountain.

Brian is President of Congregation Beth Israel in Bangor (Maine’s oldest synagogue), Treasurer for the Sisters in Arms Center in Augusta, a former paratrooper and transportation manager in the Maine Army National Guard, and a director of software development for a healthcare provider. He’s also an author, musician, and now a rabbinical student! He lives in Winterport, Maine with his wife, Leah, and their daughter, Nezzie.